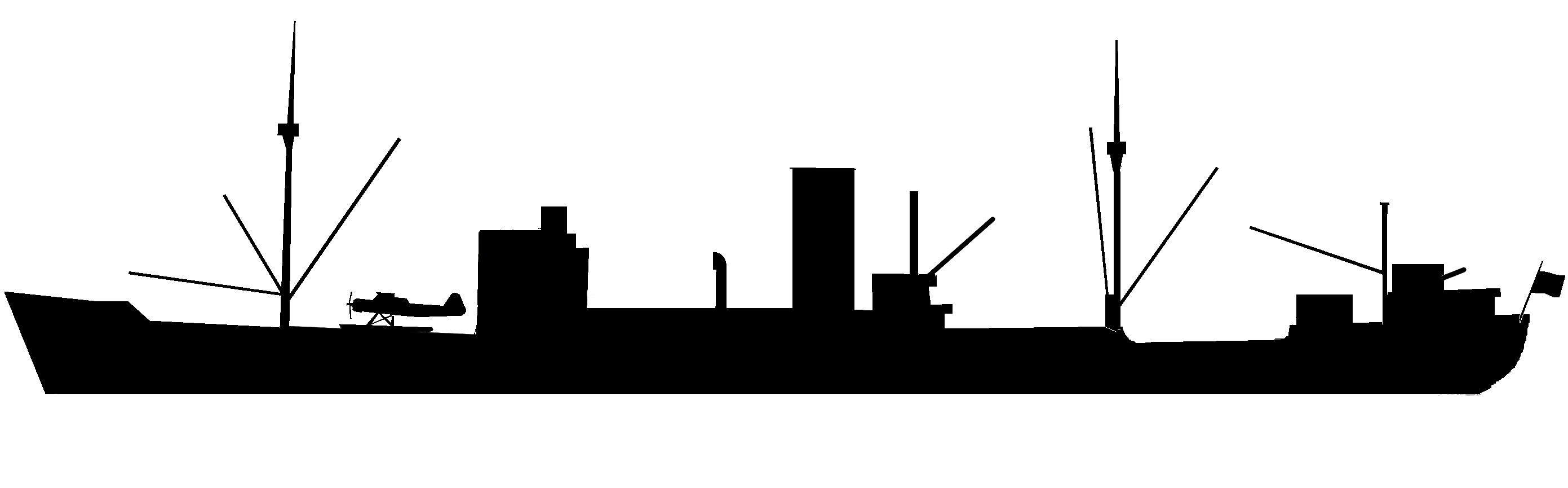

Raider Atlantis

The Atlantis was built by Bremer Vulkan in 1937 as the Goldenfels, a, for its day, modern cargo ship for Hansa Lines a German shipping company. The vessel was a conventional break bulk vessel to carry cargo of all types to ports around the world, but reportedly was constructed with features that would allow it to be converted into a raider. This vessel had a top speed of about 17.5 knots, which made it a relatively fast cargo ship for its day. Its propulsion plant was quite modern with two diesel engines driving a single propeller through a reduction gear. Only the Northern Europeans, particularly the Germans, were building large vessels with diesel engines at that time. The engine builder MAN still builds diesel engines today with horsepower ratings of over 100,000 horsepower. A diesel engine in the early thirties provided good fuel economy while requiring more maintenance than a steam plant.

When Germany was preparing for war in the late 1930’s it was decided to develop a fleet of commerce raiding ships similar to those Germany deployed in World War I. These commerce raiders are little different from the privateers of the prior centuries. Commerce raiding is a form of asymmetric warfare, for a few commerce raiders can cause a large number of naval vessels to be tied up in trying to sink them.

A commerce raider needs to carry many crew members and fitted with spaces to confine the crews of the ships that are captured. In addition, a commerce raider needs to be outfitted for extended cruising (lots of fuel and provisions and spare parts), and sufficiently armed to be quickly and convincingly subdue its prey. As during war, merchant vessels are often armed so the raider’s armament needs to be enough to convince the merchant vessel not to fight back since it would be more useful to capture the vessel and its crew rather than to simply sink the vessel.

In addition to armament, such a vessel also needs to disguise itself to approach its prey, while avoiding attention from casual inspection at sea by enemy warships. As such, a raider should have a rather “normal” appearance and be able to change its appearance to resemble other vessels, either neutral nation vessels, or vessels allied to the prey vessels. Furthermore, it should be able to hide its weaponry until the moment it is actually needed.

Finally, due to the general use of wireless communications in World War II, the vessel should be able to monitor radio communications, be able to send messages to central command and supply ships, and to perform radio warfare by sending messages to confuse the enemy or to jam enemy transmissions. The existence of radio was a limiting factor on commerce raiding. A WWII commerce raider’s greatest concern was the ability of the enemy to use radio communication between allied vessels to locate the raider and to hunt it down.

The Atlantis is an excellent example of the most modern of WW II commerce raiders with extensive hidden armaments, and with multiple methods of disguising itself by painting, by adding or removing stacks, changing masts and cranes, and even adding fake deck houses. She also had sophisticated sub systems such as double radio transmitters and even scout and light bombing planes.

Commerce raiding is still with us today, in the form of piracy rather than warfare, and the pirates are more likely to use smaller higher speed vessels, but it is entirely possible that someday a pirate nation decides to use commerce raiders like the Atlantis again. While commerce raiding is technically possible, the increase in sophistication of electronic detection and communications would make it very difficult for a commerce raider to stay at sea and to make multiple ship captures. Today with more effective communication and surveillance, the vessel would probably be hunted down very quickly after its first few captures, although finding a random ship on the ocean still is a difficult task.

Captain Bernard Rogge led the conversion of the Goldenfels into the Atlantis. Captain Rogge managed to assemble a high-quality crew and obtain good outfitting gear. The vessel departed Bremen on March 12, 1940 disguised as the Norwegian Vessel Knute Nelson passed from German waters through the British blockade into the Atlantic. Once in the open ocean, the vessel moved to the southern oceans and sank the Scientist on May 3, 1940. The vessel deployed its mines off the coast of South Africa on May 10, 1940. This was meant to force an allied ship diversion to drive these vessels into the direction of the waiting Atlantis. The deployment of the mines also was a relief to the captain and crew since it removed these explosive devices off the ship prior to any further combat activities.

Atlantis captured or sank 21 additional vessels raiding across most of the Southern Oceans. Some of the captured vessels were sunk, others taken as prize vessels and returned to German-controlled ports with cargo and captured ship crews and passengers.

A raider of the Atlantis type is most interested in capturing vessels rather than sinking them. Sinking the captured vessels deprived the allies the use of the ship and its cargo, but taking the vessel as a prize allowed the Germans to use the ship and its cargo. The Atlantis was particularly successful in this regard and managed to extend its cruise to 622 days by clever use of fuel and supplies from captured vessels.

Atlantis was even able to supply other raiders and Axis submarines during its cruise.

A cruise of this length inevitably taxes its crew, so Captain Rogge used every available method to keep up his crew’s morale. While there were no easily accessible friendly ports for the vessel’s crew to obtain shore-based leave, Captain Rogge did take the ship to Kerguelen, Vana Vana in the Tuamotu Archipelago and Henderson to allow the crew to have some shore time and to perform refit and resupply. Ironically the most severe damage the vessel sustained occurred when the vessel struck an uncharted rock while approaching its anchorage in Kerguelen.

A successful raider starts to draw attention at a certain point and the noose pulled tight on November 22, 1941 when the Atlantis was found by the cruiser Devonshire in the south Atlantic. Captain Rogge decided not to show his arms since resistance against the much more powerful vessel would be useless and not revealing the guns would prevent the allies from being able to confirm they had sunk a raider.

The Atlantis crew took to the boats and sank the ship with explosives set off by the crew (scuttling). The ship had been found while refueling a submarine, which surfaced after the cruiser had departed the area, (The cruiser had not approached the Atlantis crew since it was concerned about the possible presence of a submarine). Although Atlantis had been sunk, the crew’s adventures did not end there. The submarine took part of the crew aboard, kept part of the crew on the deck of the submarine in rubber rafts, and towed part of the crew in lifeboats, and set off for Brazil. The crew never reached Brazil, but instead were met by another submarine, then taken aboard a raider supply ship, which was also sunk by the allies, so again they were towed in lifeboats by two submarines, and eventually transferred to eight additional submarines, all of which managed to make it to occupied France, where the crew was split up for other war time duties.

Often humans are directly tied to a particular ship and in this case Captain Bernard Rogge should be mentioned as part of the Atlantis history. As a young cadet Captain Rogge had been identified as a promising officer whose interests ranged from warfare, to training, to seamanship, to maritime ethics.

While raiding can be interpreted as something sneaky or even immoral, from the first instance Captain Rogge intended to perform his assignment to the highest ethical levels possible within the context of the horrors of warfare. During the extended cruise Captain Rogge managed to maintain those standards and while he captured and sunk 22 allied ships, the cost of human life was limited to less than 50 casualties (both German and Allied) despite numerous gun battles.

Next to some good old luck, the low cost in human life was related to the planning of his captures, choices of using overwhelming force and reducing risk, his great care of the captured enemy vessel crews, and his decision to sink the Atlantis rather than to seek pointless glory at a point of no return.

Upon his return to Germany, he was promoted to Admiral and after the German surrender, due to his excellent reputation for ethics, his detention by the Allies was a mere formality. When the German military forces were reconstituted under NATO as deterrence to Soviet adventurism, Admiral Rogge became commander of all NATO ground, air and sea forces responsible for defending Northern Germany and he retired from that command in 1962. Captain Rogge died in 1982 at the age of eighty-three.

The story of the Atlantis is told in the movie “Under Ten Flags”. The vessel was also featured in a wartime issue of LIFE magazine. A LIFE photographer, David Sherman was a passenger on the Zam Zam taken by Atlantis, and his photos taken aboard the Atlantis were published in the 23 June 1941 issue of LIFE after the photographer had been sent ashore with other captives and while the Atlantis was still actively raiding.

The model

This large model was built from scratch in 2006 using a purchased fiberglass hull. From a technical point of view, this model is probably the finest in the Bahrs collection, showing a very high level of detail, imagination, technical excellence and educational usefulness. The vessel is shown disguised as the Knute Nelson, at the moment of deployment for full action with the gun hatches opened and deck gun positions being exposed, but shows her Nazi flag. (Bahrs keeps the stern of the model tucked into a corner to prevent too many questions about displaying a model that flies a Nazi flag; history and model selection are complicated). In addition to the guns, the torpedoes, the mines, and one of the float planes are also shown. In real life it is unlikely all these details would be revealed at the same time in operation, since each component would be deployed at different times in action; the model demonstrates the wide variety of equipment installed on the vessel and the complexity of keeping all this equipment operational on an extended deployment.

This model is also fitted with electrical lighting that can be turned on with switches that are hidden beneath a cargo crate on the starboard side aft of the main house. There is also a light switch that shows the reversal of the port and starboard navigation lights to confuse other vessels, but it is probably more likely that those lights would be fitted in a somewhat different arrangement on the actual vessel.